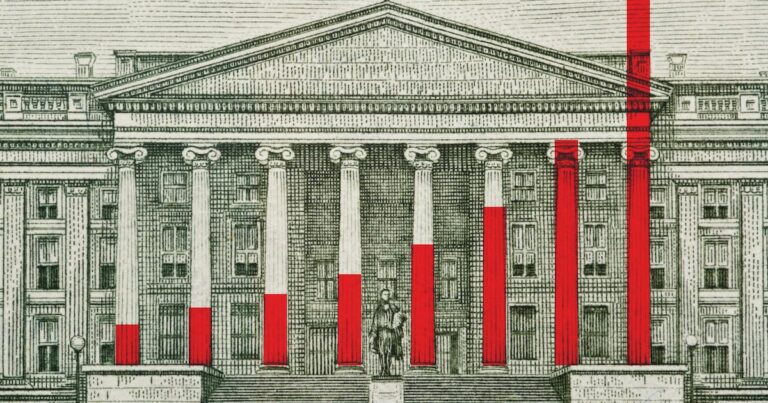

“Mushrooming national debt,” the headline says.

What followed is a question-and-answer story prefaced with the notion that, with “public debt (at) an all-time peak, you might well wonder where our national debt is heading.”

It could have come from any newspaper in 2025, but this was a syndicated piece Americans woke up to in May of 1965, more than 60 years ago.

It also illustrates one of the reasons many people may not take today’s national debt seriously.

Americans have been hearing the same thing for decades now, and yet the nation has been on a steady arc of prosperity.

Public indifference?

In an interview this week, Utah Sen. John Curtis told me he feels Utahns are more concerned about the nation’s rapidly increasing debt load than most people in the country, based on constituent comments to him. But that isn’t the case for many of his colleagues from other states.

“Being from Utah, I feel like Utahns understand this better than most,” he said. “I will tell you, though, as I talk to my colleagues around the country, they’re not hearing it at home. It’s not their No. 1 priority because of that.”

Rep. Blake Moore, who represents Utah’s first congressional district, related similar feelings. Utahns, he said, care a great deal about debt. And yet, many Americans don’t act as if the country is on the verge of economic disaster, nor with any awareness that the national debt just passed $37 trillion.

Unemployment sits at 4.1% nationally, and in Utah it’s 3.2%. On Tuesday, the S&P 500, a benchmark for the stock market, hit an all-time high of 6,309.62.

As a result, deficit cutting and long-term debt reduction efforts get little traction in Washington.

And yet the nation’s public debt today is about 124% of GDP, meaning that the nation’s debt obligations are slightly higher than the annual output of its entire economy. No one knows how high that ratio can go before a crisis is triggered. Earlier this year, Moody’s downgraded the United U.S. credit rating from AAA to AA1.

I sought out Curtis because, at the beginning of his term, he told the Deseret News/KSL editorial board he wanted to be the “tip of the spear” on Social Security reform in the Senate. I spoke with Moore because he sits on the House Committee on Ways and Means and is co-chair of DOGE, or Department of Government Efficiency, caucus.

A lack of urgency

With the budget bill now in the rearview mirror, both expressed concern over a lack of urgency in Washington.

“It’s absolutely a hindrance,” Moore said. “Because every day I wake up I see the fact that we need almost $1 trillion just to service the debt on an annual basis. That was $250 billion maybe seven to eight years ago.

“In 10 years, if we continue with a $2 trillion (annual) deficit, (while) $1 (trillion) to 1.5 trillion of that is just servicing the debt, entities, organizations, other countries, individuals, they’re no longer going to buy our Treasurys. And once they stop purchasing our Treasurys we won’t have the ability to cover that deficit.”

Treasury bonds are the primary instruments through which the federal government finances its debts.

“We can cover the deficit now. That’s why it doesn’t hurt,” Moore said. “That’s why it’s not painful. That’s why the economy seems so great. But in a decade or so, when we can’t sell enough Treasurys to cover that gap, Congress is going to be forced to either do more just straight printing (of money) and not even cover the note on the borrowing side, or we’re going to have to just make tough decisions.

“And the order in which people will vote, they’re going to make sure we have Social Security, Medicare and defense covered. That might cover all $5 trillion worth of the revenue we can pull in, because we can’t really go get $2 (trillion) to $3 trillion more in revenue. Anybody who thinks we can tax more to get an extra $2 trillion in revenue isn’t being serious. So, that’s my big concern. That’s what I go through every single day.”

Didn’t the budget bill add to the debt?

You might wonder why these lawmakers are so worried about debt after voting for the “One Big Beautiful Bill,” which is projected to add trillions to the debt. The simple answer is that they don’t believe the projections, and they believe details of the bill are misunderstood by many.

Both Curtis and Moore note that the bill largely continues current policy by making permanent the tax cuts Republicans passed in 2017.

Projections that the bill will increase the national debt over time miss the effects of this and of the nominal spending cuts in the bill, they said. Both will stimulate growth. Also, the alternative — letting the tax cuts expire — would have resulted in a tax increase that would have been a drag on the economy.

It’s a simple concept. If you want more of something, in this case productivity, you tax it less. Or, in this case, you keep from taxing it more.

“There are no models really to tell you right what’s going to happen here, but I also am strongly convinced and believe that had we let those tax cuts expire, it would have been devastating to the economy,” Curtis said. “It would have been devastating to the deficit, as well.”

Utah’s four members of the House of Representatives all signed a joint op-ed in the Deseret News enthusiastically defending their decisions to vote in favor of the bill.

“Whether you’re a server working late nights on the weekends or an electrician pulling double shifts, this bill ensures more of your hard-earned money stays where it belongs — in your pocket to use in our communities,” they said.

Perhaps not surprisingly, many economists and analysts disagree.

Writing for The Tax Foundation, Daniel Bunn, Alex Muresianu and William McBride offered perhaps the most evenhanded assessment I could find. They said the bill, by making tax cuts permanent, provides “certainty for households and stability to the structure of the tax code.”

However, they said, “The law further complicates the tax code in several ways, sending taxpayers through a maze of new rules and compliance costs that in many cases likely outweigh potential tax benefits. No tax on tips, overtime, and car loans comes with various conditions and guardrails that … will likely require hundreds of pages of IRS guidance to interpret.”

The reliability of budget predictions are, of course, subject to a host of unintended consequences and ripple effects. Utah’s political leaders are correct in saying a tax hike would slow economic output. But Curtis and Moore agree that, the bill’s pros and cons aside, Washington hasn’t really begun to tackle its overspending problem.

Social Security’s problem

If any aspect of that is going to trigger problems in the near future, it is Social Security’s Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, commonly known by the acronym OASI. With the baby boom generation aging and with the ratio of retirees to workers dwindling, the trustees’ report for 2025 says this fund is projected to no longer cover the total benefits owed to recipients in about nine more years.

At that time, the report said, the fund will be able to pay only 77% of scheduled benefits.

“The Trustees recommend that lawmakers address the projected trust fund shortfalls in a timely way in order to phase in necessary changes gradually and give workers and beneficiaries time to adjust,” the report said. It adds this warning: “Implementing changes sooner rather than later would allow more generations to share in the needed revenue increases or reductions in scheduled benefits.”

A 23% reduction in benefits would likely result in revolts and political upheaval. Older Americans tend to vote in higher percentages than any other age demographic, and younger Americans are counting on the promises of retirement benefits, as well.

A number of potential solutions to this looming problem have been floated. Perhaps the most popular would be to either raise or eliminate the cap on taxable earnings. Currently, workers are required to pay taxes for Social Security only on incomes of up to $176,100. Any earnings above that are not taxed.

Another option is to reduce benefits for the wealthy. People who earn above a certain income level would see benefits reduced until, at a certain higher income, they would disappear completely. Also, the retirement age could be raised.

These changes could be made to apply only to today’s younger workers, not to those either close to or above retirement age.

Some also are calling for an increase in the payroll tax that funds Social Security.

Earlier this month, Sens. Bill Cassidy, R-La. and Tim Kaine, D-Va., wrote an op-ed for The Washington Post arguing for the creation of an additional Social Security investment fund using “stocks, bonds and other investments.” This would be in addition to the current trust fund. They would kick-start the fund with $1.5 trillion and let it grow for 75 years, during which time the Treasury would cover the program’s shortfalls using money from other sources.

After 75 years, the new fund would be large enough to repay the Treasury for covering Social Security’s losses and still have enough to supplement payroll taxes and keep the trust fund solvent indefinitely.

It’s an idea Curtis finds intriguing. He believes answers to the nation’s problems include stimulating economic growth, but says he’s “also receptive to the idea that we do need to look for additional revenue in the right places, very, very carefully.”

He would put all those suggestions into a funding model and test different levels of each, moving them back and forth until the right mix is found.

Moore said the answer has to be bipartisan. Republicans need to realize that debt cannot be solved through economic growth alone. Democrats need to learn that it can’t be solved through tax hikes alone.

He believes that if Congress had approved President George W. Bush’s plans to allow people to invest a part of their Social Security funds in stocks and bonds, Social Security would be in a better place, and today’s retirees would have much more money.

Reasons for hope

The national debt, and the $2 trillion annual budget deficit that feeds it, may seem hopeless. It’s easy to understand why many Americans choose to ignore the problem, especially in times of relative plenty (inflation worries aside). But the problem can be simplified if it’s reduced to what experts say would be the source of the economy’s eventual undoing — the loss of confidence among investors who buy Treasury instruments.

Two years ago, the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Wharton Budget Model published a brief that predicted a loss of confidence would come when the nation’s total debt equals about 200% of GDP.

When that happens, the brief said, “no amount of future tax increases or spending cuts could avoid the government defaulting on its debt whether explicitly or implicitly.”

The key, then, is investor confidence. Even a small movement toward reducing annual budget deficits would move that in the right direction.

Curtis calls this “bending the curve to show people you’re serious.” He suggests just reducing the annual deficit to a certain ratio of GDP, which would help calm markets.

Both Curtis and Moore talk about the need for a new bipartisan commission to address debt. Similar attempts have failed in the past, including the much-touted Simpson-Bowles Commission established by President Obama in response to the Tea Party movement.

That brings the discussion back to the lack of urgency that comes during calm times.

Much has happened since that headline in 1965 about a “mushrooming national debt.” Americans have weathered seven recessions, including one about 17 years ago that we labeled the “Great Recession.” And yet the trend has been steadily upward. Household income has increased slightly, when accounting for inflation, but innovation has given consumers a host of inexpensive items that didn’t exist 60 years ago.

Yes, house prices have soared (the median price in June 1965 was $206,000 in today’s dollars), but the poverty rate has fallen from 17.3% in ‘65 to about 11.1% today.

Call this the stiff headwind of prosperity. If today’s Congress can’t overcome it, including the loud protest of special interests that try to stifle any change, a much stronger gale could be not far behind.