The Bengals have one of the worst recent track records in the NFL when it comes to first-rounders who don’t pan out. From John Ross to Billy Price to Cedric Ogbuehi, the list is long — and expensive.

Bengals Mike Brown and coaching staff discuss the upcoming season

Bengals Mike Brown and coaching staff discuss the upcoming season during their annual media luncheon.

A guaranteed four-year contract. This is the reward for becoming one of the top players in college football.

That promise isn’t a gift − it was won in collective bargaining. Under the NFL’s rookie wage scale, first-round picks are guaranteed four years of pay, regardless of injury or performance. It’s the only round where such security is mandatory.

First-round picks are drafted to fill an immediate need − not to be slowly developed. They’re thrown into high-pressure roles against seasoned pros from Day One. That’s why they burn out at a higher rate than any other draft tier. The system is built on asking these young athletes to absorb the most risk, the fastest − physically, mentally, and professionally. The full guarantee is meant to offset that gauntlet. It’s not a bonus. It’s protection for a job that breaks players early and often.

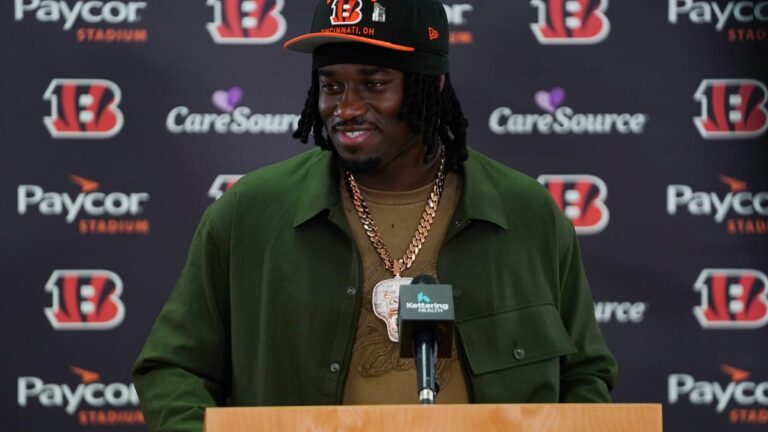

But now, the Cincinnati Bengals want to rewrite that deal. They’re trying to insert a clause into first-round pick Shemar Stewart’s contract that would allow them to void his guarantees if he’s suspended, arrested, or judged to have engaged in conduct “detrimental” to the team − even if that conduct is a misdemeanor.

That clause would give the Bengals the right to cancel Stewart’s remaining guaranteed money for something like a DUI. But let’s be honest: the real reason they want this clause isn’t fear of future legal trouble. It’s fear of another underperforming pick.

The Bengals have one of the worst recent track records in the NFL when it comes to first-rounders who don’t pan out. From John Ross to Billy Price to Cedric Ogbuehi, the list is long − and expensive. Rather than own those misses, the team is looking for a back door: a way to dump a contract if a player underperforms and gives them any off-field excuse.

That’s what this “detrimental conduct” clause does. It turns the guarantee − the thing that first-round picks earn through years of elite performance and hard-won union protections − into something conditional. And vague. And revocable.

This has nothing to do with setting a moral standard. The Bengals, like many teams, have been more than willing to play players with real disciplinary issues − as long as they perform. Vontaze Burfict, Carlos Dunlap: both had multiple suspensions, and both stayed on the field. That’s the actual precedent in Cincinnati − performance over principle.

The Bengals aren’t following NFL norms

The Bengals claim they’re simply following the “evolution” of contracts across the league. And yes, some teams have included clauses like this in recent years. But nearly all of those cases involved first-round picks with documented off-field red flags. Shemar Stewart has no such issues. The Bengals aren’t following league norms − they’re fronting for a league-wide push to erode the only part of the draft still governed by player leverage.

That leverage matters. Second-round picks get no guaranteed money at all. The only security in this system comes from being a first-rounder. If a team has serious concerns about a player’s character, then don’t draft him in the first round. But don’t draft him and try to gut the guarantee that comes with it.

This fight isn’t just about Stewart. It’s about whether the NFL can chip away at the few protections players still have by slipping “conduct” clauses into guaranteed deals and using performance as the true test − even if they never say so out loud.

The players and their union should be watching this one closely. Because if Stewart caves, the next first-rounder will be told this is now the standard. And once that happens, the protections first-rounders have relied on since the wage scale was put in place will be gone − quietly, clause by clause.

Dennis Doyle lives in Anderson Township and is a member of the Enquirer Board of Contributors.